The Secret Wife Read online

Page 9

The story began with a young country boy called Mikhail who sees a local girl, Valerina, falling off her bicycle and rushes to help. The grazes on her hands and knees are bleeding and obviously painful but she bites her lip and blinks away the tears and at that moment he finds himself starting to fall in love with her.

The translation of the text was uneven with some awkward phrasing but Kitty was soon hooked as young Mikhail explored the sensations of love: he wished he could get inside Valerina’s skin and experience her every thought and feeling so that he would never say or do the wrong thing; he was tortured with jealousy when he saw her in conversation with anyone else; he felt as though he was losing his mind to some overpowering affliction that brought more pain than it did reward. Soon his devotion paid off and she fell in love with him too but he found it hard to believe. His emotions swung from exhilaration one moment to anxiety the next and, without meaning to, Kitty found her thoughts wandering back to her early days with Tom.

She had first spotted him playing his songs to a small group at the students’ union, and she liked his absorption in the music, his unruly hair, the striped Pierrot t-shirt and braces he was wearing, and his grin when everyone applauded at the end. For a few weeks she stalked him, looking for a way to introduce herself, but in the end he made the first move, appearing by her side when she was placing an order at the bar and saying, cheekily, ‘Mine’s half a bitter.’

‘Can you add half a bitter?’ Kitty asked the barman, and Tom was shamefaced.

‘I was joking. You don’t have to buy me a drink. Let me give you the money.’

She insisted on paying and he followed her over to join the group she was with, introducing himself around the table. He was affable and everyone seemed to like him, but Kitty was so attracted to him at close range that she could barely focus on the conversation. She longed to place her hand on his thigh, nestle into his shoulder, press herself against him. She’d never felt such lust for anyone and wondered how he could be oblivious to the sheer force of it. But it seemed he wasn’t: at the end of the evening, as the others rose to leave, he took her hand and whispered, ‘Can I come back with you please?’

Kitty was staying in student accommodation, where they weren’t supposed to have overnight guests, but she sneaked him in. As soon as the door closed behind them they ripped off their clothes and spent the night in a frenzy of steamy, compulsive sex that left her head feeling as though it was stuffed with cotton wool. When she got up to make tea in the morning, Tom said, ‘This is a little awkward, but I’m sorry, I didn’t catch your name.’ And they both collapsed in giggles; it still made her giggle now. And then she remembered Karren with the double ‘r’ and stopped abruptly.

She got up and laid the book to one side while she waded into the cool waters of the lake. It was shallow close to shore but she always swam out until the cabin was barely distinguishable amongst the dense woods that surrounded it. From that distance she could see how isolated it was, with no other man-made structure for at least a mile on either side.

It was three weeks since she arrived at Lake Akanabee and she hadn’t been in touch with anyone back in England. She knew this might be construed as eccentric behaviour but the solitude was feeding something within her. She could feel herself getting stronger with each day of self-sufficiency and she supposed before long she would be tough enough to go home and deal with her marital problems. Perhaps she could also deal with her discontent about the whole fabric of her life. She was thirty-five years old and it was time to decide how she wanted to spend the next few decades. If she wasn’t going to be with Tom, she should look for someone else before the wrinkles and grey hairs set in. She shook her head to dispel this image. The thought of being with another man filled her with dismay: all that adjustment as you learned someone else’s tastes, their sleeping habits, their moods …

She dived down through the clear, cool water. She could see the bottom but it was further than it looked and she had to turn and come up for air before she reached it.

The heat was too intense for hard physical work so Kitty decided to take a day off and immerse herself in her great-grandfather’s novel. It was strange to get a glimpse of his personality through the story while living in his cabin and walking in his footsteps. She felt a kinship with him as she lay in the shade of the trees he must have looked up at, and read Interminable Love, his first novel.

Civil war separated Mikhail and Valerina when their families were sent to opposite sides of the country and he was forced to fight, but their love remained strong as ever. Neither would marry; neither could contemplate being with anyone else, so they lived half-lives shadowed by the memory of their first and only love.

As the sun set, Kitty lit a fire, cooked herself a burger on a rack set over the flames, opened some wine, and continued to read in the orange flickering glow. In the final chapter, Mikhail tracked down the remote Siberian village where Valerina now worked on a collective farm. He asked around to be told she was out in the fields operating one of the new-fangled tractors that had just been delivered. Modernity was often portrayed as evil in the novel, with machines taking the place of people in a metaphor that suggested the unquestioning obedience to the regime of its cowed citizens. Mikhail spotted Valerina from afar and began to run towards her. She saw him approaching, realised who it was, and tried to turn off the tractor’s engine – but something went wrong and it started to accelerate. It was heading straight for Mikhail so she pulled down hard on the steering wheel and as the vehicle turned it toppled onto its side, crushing her underneath. Mikhail struggled to lift the tractor but it was far too heavy. He called for help but there was no one in earshot. Valerina’s injuries were too severe for her to survive so he lay on the earth beside her, kissing her face as she slipped off into the blackness of death.

It was something of a clichéd ending but tears were streaming down Kitty’s cheeks. She wiped them on the hem of her t-shirt but couldn’t stop crying and soon she was sobbing out loud, with huge painful spasms that hurt her chest. She hugged herself and buried her face in the crook of her elbow, crying with the abandon of a child. She hadn’t even cried like this when her parents died. Was it because she was tipsy? What was this about? And as soon as she asked the question, she knew: it was because she missed Tom. There was so much she wanted to tell him. She wished he could see the work she had done on the cabin. She wanted to tell him about this Russian great-grandfather who had been an author. Perhaps he could help her to decide how to make her life more fulfilling … But he was not ‘her Tom’ any more. She couldn’t talk to him because the huge matter of his infidelity lay between them and until she could decide how to deal with that it was easier not to be in touch at all.

As she lay in bed that night, wrung out from crying, Kitty’s thoughts turned again to Dmitri Yakovlevich: he must have been a romantic soul to write so movingly about love. Why had he been living in such a remote spot? Was he alone there? Did he ever come to London to meet his great-granddaughter or was he too elderly and frail to travel by the time she was born? His bed had been in the spot where she now lay, in a corner beneath the window, so he must have looked out at the silver birch tree branches swaying in the moonlight just as she was doing now. She didn’t believe in ghosts but at that moment she felt as if she could almost sense his presence, standing a few feet away, calmly watching over her.

Next morning, she drove to the coffee shop with her laptop and tried to find out more about Dmitri. She went to an ancestry website she had used for journalistic research at college. It had a US immigration section, but she couldn’t find anyone with Dmitri’s name. She tried her grandmother Marta’s maiden name and the search engine whirred and finally came up with a child of eight years old, who had entered the United States in 1934. That sounded about right. Travelling with her, in a second-class cabin, were her mother, Rosa Liebermann – a name Kitty had never come across – and her brother Nicholas, aged nine. She’d heard there had once been a great-uncle Nichol

as, so this must be them. She looked further up the page and there it was: Dmitri Yakovlevich Malama, aged forty-three years and four months. Was his real surname Malama? Why had he used Yakovlevich on his novels? The party’s place of departure was given as Berlin. It took Kitty only a few seconds to speculate that the reason for their departure from Germany in 1934 might lie in Rosa’s Jewish-sounding surname. But how had Russian-born Dmitri come to be in Berlin in the first place?

She tried several other searches but with no more success. She couldn’t find where Dmitri and Rosa had lived on arrival in the US, what schools the children had attended, or where he had worked.

She closed the computer and drove to Indian Lake for some pots of varnish. She wanted to cover the entire cabin with a weatherproof coating while the weather was dry. The man in Lakeside Country Stores recommended the type he said was most effective against the cold, snowy winters in these parts. He was respectful now, as if he’d accepted she knew what she was talking about.

While she worked on the front wall that afternoon, she heard an outboard motor on the lake and turned to see a mahogany-skinned, silver-haired fisherman close to the shore. She waved and walked down to the broken jetty to greet him.

‘Y’all bought the cabin, have you?’ he called, squinting up at it.

‘I inherited it,’ she explained. ‘My great-grandfather used to live here.’

‘Well, I’ll be!’ he exclaimed. ‘You’re Dmitri’s kin? I thought that cabin was a write-off but he would be happy to see you doing it up all nice.’

Kitty blinked. This man had known Dmitri. Rather than spend an hour on the internet, why had she not thought to ask around locally? ‘Can I offer you a beer? Or a coffee?’ she asked.

‘A beer’d be nice.’ He tied his boat to one of the broken struts of jetty and leapt to shore. ‘Name’s Bob. I live over the far side.’ He gestured.

Kitty fetched two Buds and a bottle opener and they sat on the grass facing the water. He offered her a Marlboro and lit up himself when she refused.

‘It’s funny you should come along because I’ve been trying to find out about Dmitri,’ she began. ‘Were you two friends?’

Bob shook his head. ‘We said hi when we bumped into each other at the store, but he never invited me here and I never invited him to mine. We lived our own lives.’

‘Did his wife stay here with him?’

Bob frowned. ‘I never saw a woman. Just him padding around on his own, with his dog at his heel. He was a writer so I guess the solitude suited him.’

‘I read one of his books yesterday. Until recently I had no idea we had a writer in the family.’

‘Yeah, I’ve got all his books. He gave them to Sue and me as a wedding present. My wife likes reading but I’ve no time for it.’

‘That’s amazing!’ Kitty was delighted. ‘Have you still got them? Do you think Sue would mind lending them to me?’

‘I’m sure she wouldn’t mind.’ He glanced over towards his home and chuckled. ‘See that glint in the trees over yonder? It’s probably her looking out for me with the binoculars. She’ll be wondering what I’m doing drinking beer with a pirtty lady.’

Kitty saw a dancing point of light in the direction he indicated. She hadn’t considered anyone might be watching through binoculars and flushed to think they could have seen her wandering around naked.

‘You not lonely here?’ Bob asked. ‘Is your boyfriend coming over?’

‘My husband’s back in England,’ she said. ‘I’m keeping myself busy, as you can see.’ She waved an arm at the half-finished coat of varnish.

‘Let me give you my cell,’ Bob said. He scribbled the number on the back of the foil in his cigarette pack with a pen from his shirt pocket. ‘You call if you need anything. It’s a remote spot for a young girl like you.’

She was touched by his concern. She felt completely safe in the cabin but it was good to have a neighbour’s number in case of an emergency. When he left, he promised to return in a day or so with Dmitri’s books.

She went back to her varnishing, annoyed to see that the stretch she had already coated was now covered in dead and dying flies, like the bloody aftermath of some miniature battle.

Chapter Sixteen

Moldavia, December 1916

By the time Dmitri arrived in Moldavia, a hilly country squeezed between the Russian Empire to the East and the Austrian Empire to the West, winter was closing in. There could be no fighting while mountain passes were closed due to thick snow and the ground was too hard to dig trenches, so all sides hunkered down. Dmitri was furious to find he had travelled hundreds of miles south simply to spend the next few months living on meagre rations in an army bunker when he could have been in Tsarskoe Selo, close to his beloved wife. It was characteristic of the complete lack of foresight amongst the Russian high command.

Looking back, his wedding seemed like a dream. He still could not believe that he was married to the most beautiful, most talented of the Romanov grand duchesses. Tatiana’s letters came regularly, and there was a new air of intimacy about them. She confided in him about family matters that she would have considered disloyal to discuss before their marriage:

Olga finds it too hard to continue working in the hospital: she does not have the stomach for watching operations or cleaning wounds. Her nerves are suffering from the prolonged absence of our father and brother, and she has transferred all her attention to Mitya (yes, he’s here again). I swear she talks of nothing but him and I am fed up hearing of his every word and breath! Meanwhile, she never asks about you, sweet Malama. I think she is jalouse of our closeness and prefers not to hear of it.

She wrote that Anastasia and Maria fought more than ever, sometimes wrestling on the floor pulling each other’s hair and having to be separated by force. She wrote that her mother was taking increasing doses of Veronal for her many ailments, which made her so sleepy that Tatiana invariably had to attend the tedious refugee committee meetings on her own. And always she wrote with concern for Dmitri’s safety, begging him to keep warm and stay out of harm’s way.

While she was anxious about him, he was becoming increasingly alarmed about the safety of the Romanovs. Now he was back amongst soldiers, he realised many were saying openly that the royal family had to be overthrown. Nicholas no longer had the support of a large number of his men, who were fed up being sent on suicide missions against a better-equipped, better-managed opponent. The territorial gains made by General Brusilov’s advance had already been reversed by the Austro-German Ninth Army and there seemed little hope of victory on that front. Meanwhile the letters the men received from their families back home told of dire food shortages and dread of the starvation winter would bring. Even the army survived on what they could hunt in lieu of regular rations. And now that Nicholas was at the front and Alexandra was in charge in St Petersburg, there were louder rumblings that she was too much influenced in her decisions by Rasputin.

‘I reckon they are German spies who send Russian military secrets to the enemy; that explains why the Germans are always one step ahead,’ Dmitri heard a soldier telling his friends. He wished Alexandra had a wider circle of advisors, but she had always remained aloof from the St Petersburg aristocracy and trusted no one except her husband and Rasputin, laying them open to all sorts of allegations.

On the 18th of December, Malevich came to Dmitri’s tent with alarming news from the city: Rasputin had disappeared and foul play was suspected. Instantly Dmitri was worried for Tatiana’s sake, knowing how distressed she would be, and quickly sent off a letter expressing his sympathies. He had never met the man: an opportunity had not arisen for Tatiana to introduce them. Despite his instinctive mistrust, he understood how strongly the family felt they needed him and knew the loss would hit them hard.

The following day a letter came by messenger from Tatiana telling him the horrific news:

Uncle Grigory has been murdered, hideously murdered, and it seems it happened at the home of Prince Felix Yusupov

, who is married to my cousin. I can hardly bear to write the words, but perhaps you know already because it is all over the newspapers the men were reading in the hospital this morning. One of them even showed a gruesome photograph of his corpse with an eye gouged out. His poor eye! Dmitri, they say he was poisoned, stabbed, shot and still he did not die until they drowned him in the Malaya Nevka River, where his body was discovered beneath the ice. What has happened to our country? Why would anyone do this to a holy man? I simply don’t understand …

Dmitri guessed Yusupov might have done it in an attempt to protect the family from the insidious rumours about the holy man. If only it would stop the rot, it would be worthwhile, but he couldn’t say this to Tatiana so he sent back a note repeating how sorry he was and how much he wished he could be there to comfort her in person.

The following day another letter came, only slightly calmer than the last:

I am comforting myself by looking through a notebook I have kept over the years in which I wrote down his wisest teachings. One day I will show it to you, Dmitri, so you understand his true goodness. Mama is inconsolable at the loss. She says Uncle Grigory is a martyr who deserves to be sanctified, and begged that he should have a state funeral. Papa, who has returned from the front, disagreed and this morning he arranged a simple service at which we all paid our respects. Mama laid an icon on Uncle Grigory’s chest before the coffin was sealed and we dropped white flowers in his grave as we said our desolate farewells … I just don’t understand a world in which such a thing can happen. I wish you could explain why …

Dmitri hoped word of this funeral did not become public. Tatiana had no idea about the mood of the populace, which turned uglier by the day. The common soldier was jubilant about Rasputin’s murder, while in the streets of St Petersburg he heard they lit candles in celebration and chanted ‘A dog’s death for a dog’.

The Collector's Daughter

The Collector's Daughter The Lost Daughter

The Lost Daughter Jackie and Maria

Jackie and Maria The Affair

The Affair Love...Maybe

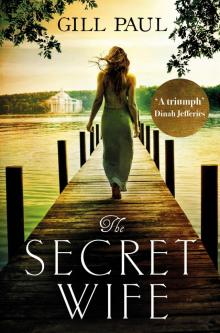

Love...Maybe The Secret Wife

The Secret Wife No Place For a Lady

No Place For a Lady Another Woman’s Husband

Another Woman’s Husband World War I Love Stories

World War I Love Stories World War II Love Stories

World War II Love Stories