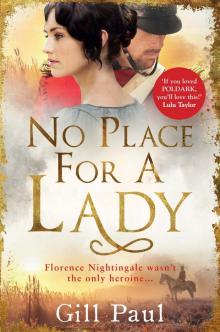

No Place For a Lady Read online

Page 15

Kate examined her and sponged her brow with cool water. ‘I don’t think it’s scarlet fever,’ she said, and Dorothea confirmed she had already survived a bout in childhood. ‘They have malaria in these parts.’

‘I don’t feel feverish. Please … I can feed myself.’ Kate had lifted a spoonful of arrowroot towards her lips.

‘If you’re sure.’ Kate gave her the spoon and watched as she swallowed the glutinous mixture.

‘I’m feeling much recovered. It’s been most kind of the two of you, but I think if you don’t mind that I need to be on my own, to rest.’

When they were finally persuaded to leave, Dorothea lay with grim thoughts swirling round her brain. If the men had given her a disease down below, surely she would not feel feverish so soon? She wasn’t sure whether sexual congress had taken place or not – could it have? She hadn’t bled, and she’d heard the rupture of the hymen caused bleeding. Either way she felt deeply ashamed. What if she had conceived a baby? She didn’t even know the nationality of the men, hadn’t recognised the tongue they spoke. They were simply ruddy-skinned sailors from a foreign land who thought she was for sale, as no doubt many of the other women living in those basements were.

Dorothea stayed in bed for the next four days, in a state of shock and misery. Was she permanently damaged by what they had done to her? At home she might have confided in Miss Alcock, but she felt she did not know her new companions well enough and so she kept it to herself. And all the time she felt sick with fear that Lucy might have met a similar fate – or worse.

Elizabeth and Kate brought her light meals of soup and boiled chicken along with news from the world outside. One day, they were taken to visit a nearby naval hospital and returned with some of the men’s clothes to launder and repair. Dorothea offered to help so her friends brought a bundle of garments to her room, where they sat sewing companionably. Stitching seams and darning holes helped to occupy Dorothea’s mind while she recovered from her ordeal.

Miss Stanley had continued to negotiate with Miss Nightingale about the employment of the nurses she had transported to Constantinople and at last, after two weeks in the Hôtel d’Angleterre, they were told they would be taken to the Barracks Hospital at Scutari the following Sunday. Dorothea flushed at the news and her heart beat faster, but she told herself she must go. It was the reason she had come to the Turkish lands. This time she would be with a group of women and there would be safety in numbers. Her fever had lifted, she no longer felt pain down below, and she yearned to keep busy, so she insisted she was well enough to accompany the party.

They sailed from the same jetty but in a much larger boat, with room below deck for the women, all forty of them, to shelter from a light shower that caused a stunning rainbow to arc across the Bosphorus from west to east. She had not told anyone of her previous visit so had to pretend to share the women’s revulsion at the dead dog still lying on the path, and at the stench, even more vile than she had remembered, which met them as they approached the hospital. Dorothea didn’t glance in the direction of the cellars, resolved not to be afraid. It crossed her mind to worry that her attackers might appear and recognise her, might even accost her, but she reassured herself that they had hardly seen her face. Thank heavens for small mercies.

Instead of being taken to meet Miss Nightingale, the party were shown by a nun to some rooms in a tower at the corner of a quadrangle where they would sleep twelve to a room, and where their luggage could be left. There were beds but no chairs or tables and just matting on the floor. The nun explained the brown basin was for washing, the wooden bucket held clean water and the tin pail was for dirty water, and she showed them where to empty their bedpans.

The foul smell was still in evidence but was not as strong indoors. The nun informed them that nurses were not permitted to leave the building, and Dorothea was greatly relieved. Each was given a sash with the words, ‘Scutari Hospital’ embroidered in red thread to wear over their uniforms, signifying their right to be there.

Mrs Bracebridge, whom Dorothea remembered from her initial interview, appeared and requested that some volunteers go with her to help in the linen room, so Dorothea stepped forward. There was no sign of recognition; Mrs Bracebridge turned briskly and led them down a long corridor and up a flight of stairs to a large room that was packed almost from floor to ceiling with what looked like dirty old rags.

‘These were sent by the British public after Miss Nightingale complained we did not have enough bandages. As you can see, most are unusable, but your task is to salvage the fabric that will do, wash it and cut bandages from it.’

‘When might we see some patients?’ Elizabeth Davis asked.

Mrs Bracebridge seemed surprised. ‘I doubt you will see any patients. Miss Nightingale is very careful in her selection of nurses. If you should have cause to go onto one of the wards, note that you must not under any circumstances talk to the men. It is quite forbidden.’

‘That’s ridiculous!’ Miss Davis had no fear of authority and always seemed to be the one who spoke up for their party. ‘Those poor boys are far from home, they’re injured and in pain, and talking to a motherly British woman would bring them much-needed comfort. What sort of a rule would forbid that?’

Mrs Bracebridge glared at her. ‘It’s a rule which if you break it will result in you being shipped home straight away, that’s what. Dinner is at seven in the dining hall. Carry on, ladies.’

When she’d gone, the women glanced at each other and burst into a fit of giggles.

‘I’ve met her sort before,’ Kate Anderson said. ‘The ones who think themselves superior in intellect to the rest of us, when it is far from the truth.’

‘I hear Miss Nightingale is something of an autocrat,’ another nurse butted in. ‘She has already sent home two nurses who went out with a male orderly to see the sights, and came back with the slightest hint of alcohol on their breath.’

‘It’s said she doesn’t like those who spout religion at the bedside,’ Elizabeth Davis remarked. ‘I can agree that were I lying in pain with a festering wound the last thing I should wish would be someone praying over me. However, our party includes nuns of both Anglican and Roman Catholic persuasion. Must they keep their prayers to themselves in Miss Nightingale’s wards?’

‘It’s probably for the best,’ Kate Anderson answered. ‘She doesn’t sound like the kind of person you can reason with.’

Dorothea didn’t agree but didn’t say so. From everything she had read in the press she had formed a very favourable opinion of Miss Nightingale. It seemed she was a woman who was not afraid to speak up in order to get her own way, and that was a rare quality. Doctors could be high-handed and autocratic in Dorothea’s experience, yet somehow they bowed to the will of this indomitable force of nature. She might make enemies amongst politicians and bureaucrats but it was said that the wounded soldiers adored her and spoke of her almost as a ministering angel who patrolled the wards at night with her lantern. Dorothea was dying to meet her and would have liked nothing more than to engage her in conversation about modern medical practice. If only they could be friends.

At dinner that evening, she sat by a nurse who had travelled out with the first group last November, who told her of the squalor in the barracks when they arrived: ‘They say there was a rotting corpse of a Russian soldier in Miss Nightingale’s own room, and vermin everywhere. The first thing we did was scrub the entire hospital area from floor to ceiling, then we washed the men as well, cutting their hair to get rid of the lice and getting the authorities to supply clean shirts for all. She’s a hard taskmistress but she certainly gets results.’

It was two days later when Dorothea first set eyes on Miss Nightingale. A small party of women swept past her in a corridor and Mrs Bracebridge caught Dorothea’s arm.

‘Come with us. We need some help carrying supplies.’

Dorothea tagged along behind, noting that there was a male orderly in the group and he was holding a sturdy iron bar. They

walked across the quadrangle to another corner of the building then up a staircase to a wooden door. Mrs Bracebridge tried the door then turned to a tall woman with short-cropped brown hair and said, ‘It’s locked, Miss Nightingale.’

With a start Dorothea realised this was the famous heroine of whom she had read in the newspapers.

‘I thought so,’ Miss Nightingale said. ‘Joseph – if you wouldn’t mind.’

She stepped back and watched as the orderly began to force the door with his iron bar. She was slender, Dorothea noted, with intelligent eyes, and her hair had a rich auburn hue. Miss Nightingale noticed her watching and the eyes swept over her briefly.

Once the door was open, she marched inside and began to issue orders: ‘Joseph, you take that crate of port wine. Selina, look for scissors; we desperately need more scissors. You,’ – she pointed at Dorothea – ‘take that box of soda crystals and follow the others.’

Dorothea had lifted the box and turned to leave when a grey-haired gentleman in uniform stormed up. ‘Miss Nightingale, not again! What do you think you are doing? This is a British government store and you have no right to break into it.’

‘I have every right when I am treating soldiers fighting for the British army. Do not attempt to obstruct us, Mr Wreford.’

A fierce argument ensued but whilst berating him, Miss Nightingale waved a hand indicating that Dorothea and the others should continue to remove the goods, and so they did.

‘Why must she fight for essential supplies?’ Dorothea asked another nurse as they made their way back to the wards.

‘It’s been like this all along. The officials here do not seem to think nurses are necessary and have tried to thwart Miss Nightingale at every turn. Fortunately she is well able to cope with them and if they become too bothersome she merely complains to Mr Herbert, the war minister, who is a close friend. She is quite indomitable.’

Dorothea grinned. Miss Nightingale was very well-spoken and obviously from a good family, but she had no compunction about speaking her mind in the face of authority. Back home in decent society she could not have been in the company of men without a chaperone, but here she could give as good as she got when dealing with bureaucrats. Dorothea wondered briefly what Miss Nightingale would have done had she been attacked by two ruffians in a cellar and imagined the ferocity with which she would have responded. If only Dorothea had managed to fight harder; despite her determination to forget, she was plagued by the memory of the assault, and the guilt and fear that accompanied it, the feeling that she had given in too easily.

There was no doubt that Miss Nightingale had greatly improved circumstances in the Barracks Hospital, having had it scrubbed from top to bottom, and throwing open windows to let in fresh air, but still the corridors that served as wards seemed grim. When she glanced in, Dorothea was shocked to see long rows of men with only a narrow space between them, most looking half-dead; every morning bodies wrapped only in sheets were carried out by orderlies for the mass burials that took place in the nearby graveyard at one o’clock daily. She was itching to be allowed onto the wards to help, but days went by when her group were merely tasked with rolling bandages, mopping floors, or mending.

Among the nurses, Miss Nightingale was the main topic of conversation and opinion was divided on her merits. As they ate their evening meal – generally coarse bread, rancid butter, sinewy meat and tea without milk – they grumbled non-stop about their famous superintendent.

‘She has sumptuous three-course meals using gifts sent by the British public. There’s a store cupboard full of food intended for wounded men that finds its way into her belly instead.’

‘In my opinion, she’s not much of a nurse. She’s got no time for dressings but you can’t keep her away from the operating theatre. I heard she knows more about amputations than many a surgeon.’

‘Don’t you think it’s hypocritical that she bans us from the wards after eight of an evening to avoid the risk of any sexual contact in the hours of darkness, but she doesn’t hesitate to sail around herself, with no concern for her own reputation?’

On the positive side, Dorothea heard that Miss Nightingale sat long into the night writing letters to government officials agitating for further supplies to be sent, and to the mothers of every single soldier who died at the hospital. Her critics found her lacking in empathy and overly self-important, but Dorothea could well imagine how much a grieving mother would treasure a letter from her. Back in Britain she had become the most famous figurehead of the war, in the way that commanders such as Wellington or Nelson had been in previous wars. Her letters to newspapers swayed public opinion and forced politicians to accede to her demands or face an outcry.

One morning as she made her way to the laundry room, Dorothea realised a ship must have arrived with more wounded soldiers from Crimea as stretcher after stretcher was being carried to the wards. The men were in a shocking state: filthy, with bloody bandages falling off their wounds, eyes staring wide from pain and shock. They stank of vomit and the distinctive rotten-apple scent of gangrene. There were so many – fifty, sixty, seventy – that it would take Miss Nightingale’s staff hours before they reached each one and Dorothea instinctively followed the procession to see if she could help. In the wards where the men were being set down, every nurse was worked off her feet and after a brief hesitation, Dorothea crouched by the patient nearest to her. He had dressings on a shoulder and a leg wound and was semi-conscious. She pulled back the leg dressing carefully and nearly retched at the sight beneath: dozens of tiny white maggots were wriggling within the wound. Bile rose in her throat. This dressing could not have been changed for days, giving the flies time to lay their eggs and for said eggs to hatch.

Dorothea went to the nurses’ store, found a basin and a pair of tweezers, then returned to extract the creatures one by one. She lost count of the number of maggots she removed but her basin was almost full by the time she had them all. She took the basin to a nearby kitchen and poured boiling water over them to make sure they perished, then returned to dress her patient’s leg with lint and oilskin. His shoulder did not have an open wound but was dislocated, the bone sticking out at an awkward angle, and she was able to arrange a sling to support it so it would not cause so much discomfort. She washed him and pulled on a clean bedshirt then tucked a blanket around, whispering that a doctor would see him presently. He mumbled something and she held her ear close to his lips. He repeated the word: ‘Mother.’ Dorothea wasn’t sure whether he was asking for his mother or he thought she was his mother, but she patted his hand kindly and said ‘Yes, you are safe now,’ before turning her attention to the next patient.

This one was a young lad, and he was tearful: ‘I’m going to die, and my father and mother did love me so,’ he sobbed. He had lost his left arm and right hand, and was greatly emaciated since no one had thought to feed him and he could not feed himself. His back was covered with bedsores where he had lain untended on the ship. The wounds were still clean, at least, so Dorothea reassured him.

‘Be brave, and you will see your parents again.’ She fed him a spoonful of cod liver oil and a spoonful of lemon juice followed by some beef tea and arrowroot mixed with egg and milk for sustenance. After that she cleaned and dressed the sores, and by the time she finished he seemed calmer. A full stomach always helped, in her experience.

In all, she had worked on eight patients before she was spotted. Mrs Bracebridge stormed over to challenge her: ‘What on earth do you think you are doing?’

Dorothea explained that she couldn’t bear to see these men wait any longer for attention. It was clear no one had looked at their wounds since they were treated on the front line, probably at least a week earlier.

‘Well,’ Mrs Bracebridge sniffed, ‘you can be sure Miss Nightingale will hear of this.’

She didn’t ask her to stop, though, so Dorothea carried on working until dinner hour. At the meal that evening, Elizabeth Davis introduced her to Mrs Eliza Roberts, a stern-looking

nurse who before the war had been a sister at St Thomas’ Hospital in London for twenty-three years.

Elizabeth seemed excited: ‘Mrs Roberts tells me that she heard three officers’ wives of the 8th Hussars went to Crimea with the troops. One of them was a Mrs Fanny Duberly, wife of the quartermaster. She doesn’t know the names of the others but it seems likely your sister was among them.’

Dorothea clasped her hand to her mouth, before recovering her wits enough to say: ‘How good to meet you, Mrs Roberts. I wonder, what was the source of your information, and when did you come by it?’

‘Dr White of the 8th Hussars happened to mention it when he was down here collecting supplies for the army hospitals they are establishing in Crimea. That was just before Christmas.’

‘Did he say anything about the other two women? Their ages, perhaps, or their appearance?’

‘Yes … He mentioned that one of them was very young; far too young to be travelling with the army, in his opinion. And blonde. I’m sure he said she was blonde.’

‘That’s Lucy!’ Dorothea didn’t know whether to feel relieved that Lucy had survived the cholera outbreak in Varna, or alarmed that she was now up on the front line of the war. Her overwhelming feeling was relief, though. She was narrowing down the search, getting closer to finding her sister every day. With any luck they would soon be reunited. ‘Thank you so much. I’m very grateful to you for sharing this information.’

‘There is also bad news,’ Mrs Roberts said. ‘Miss Nightingale would like to see you in her rooms at ten o’clock this evening. She wants to have a word.’

Dorothea knocked on the door of the room in the north-west tower that Miss Nightingale had made her base, and entered on a sharp command of, ‘Come in.’ A concertina-style Turkish fanoos cast a glow around the bare walls, and there was a bed in one corner. Miss Nightingale dipped her quill pen into an inkpot and carried on writing furiously, so Dorothea stood waiting. There was nowhere to sit down and no such invitation was issued.

The Collector's Daughter

The Collector's Daughter The Lost Daughter

The Lost Daughter Jackie and Maria

Jackie and Maria The Affair

The Affair Love...Maybe

Love...Maybe The Secret Wife

The Secret Wife No Place For a Lady

No Place For a Lady Another Woman’s Husband

Another Woman’s Husband World War I Love Stories

World War I Love Stories World War II Love Stories

World War II Love Stories